Difference between revisions of "Ci'Num scenario 4: 100,000 Flowers"

DanielKaplan (talk | contribs) m |

DanielKaplan (talk | contribs) m (Ci'Num scenario 4: Hundred Flowers moved to Ci'Num scenario 4: 100,000 Flowers: Scenario renamed) |

(No difference)

| |

Latest revision as of 16:07, 18 December 2007

Scenariothinking.org > Ci'Num 07 Homepage > The 2030 Scenarios

|

|

Position in the scenario tree

- Will we have the global organizational capacity to address the overshoot? - Yes

- What is the primary constraint of human activities? - Resources

- What are the main mechanisms for organizing large scale systems? - Markets

Initial Description

A combination of widespread innovation and bottom-up initiatives at local and global scales produces significant changes in energy consumption and production patterns: decentralized energy systems, substitution of products by services, innovative materials in everything from building to clothing to transportation, "cradle-to-cradle" product design, etc. Consumers strongly reward eco-friendly corporations and punish the others, helped by evaluation tools as well as by private and public labeling mechanisms. Networks become the primary infrastructure, and the non-material component of economies becomes the main source of wealth, trade and growth. Markets and co-operative initiatives compete in achieving desirable goals for all. Global initiatives are mainly directed towards free trade and open markets; powerful, pervasive and mostly free communication networks; and education, whose role and process change deeply. Individuals and groups form the fabric of society, lowering levels of solidarity between groups or with disenfranchised individuals. Armed conflicts decrease while global crime becomes a major, almost recognized force. Diversity and autonomy are primary values at the expense of more common values. Technology developments are targeted at human enhancement, peer-to-peer communications, and empowerment. Crises and catastrophes are more difficult to manage but their occurrence does not destabilize the overall system.

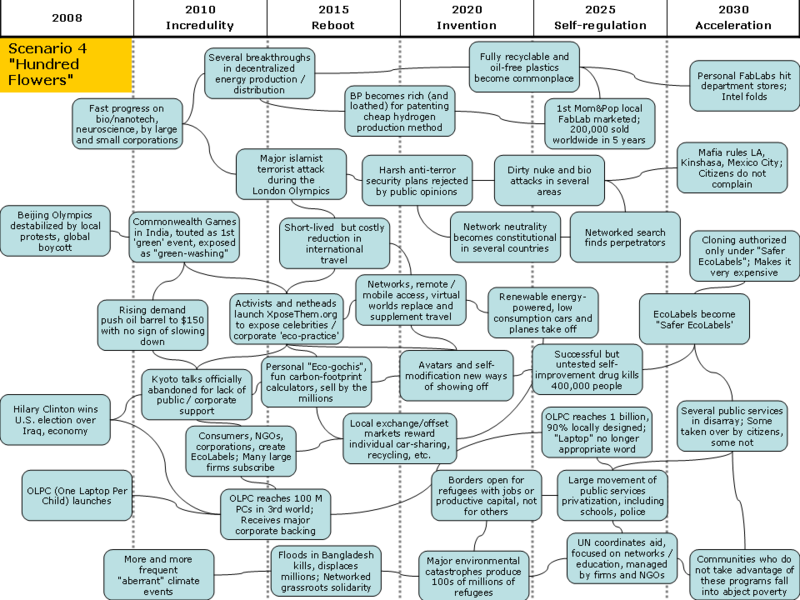

Timeline

(click image to see it full-size)

Full scenario

"Choke Beijing or choke in Beijing!" That was the initial slogan of the massive, grassroots boycott against the Beijing Olympics which, from the beginning of 2008, spread via the Internet through most of the post-industrial world. China, they claimed, had no respect for human or workers rights; it was dumping its way into others people's jobs; it supported dictatorships in order to secure oil; and it was becoming the biggest CO2 emitter in the world…

Apparently, the protest had little effect. Only two minor countries officially joined the boycott. The media were there, although its reporters had instructions to look slightly beyond the stadiums. Few large advertisers withdrew their support, and these were quickly replaced by others.

The show went on, unaware that something deeper had begun.

Incredulity

The trouble surrounding the Beijing Olympics illustrated a growing feeling that something was very, very wrong with the world's environment, and that politics and economics were responsible for it. China was only a scapegoat, albeit a large one. When bloggers, followed by the media, pieced the information together, a series of aberrant climate events throughout the globe began to make sense: Saharan heat and drought in Eastern Europe, tropical rains in Britain, roofs around the Gulf of Mexico were blown off by hurricane after hurricane… And the sharp rise in gasoline and electricity prices was taking a toll on everyone's wallet.

This (and Iraq) was enough to carry a reborn-environmentalist and progressive into the White House in the beginning of 2009. There was hope. Leadership in the U.S., France and Germany, joined by a growing number of prominent corporate leaders, were all focused on the environment. But it quickly became clear that they could not deliver. When tough decisions had to be made, such as taxing polluting activities - intensive agriculture, car use and the like - they showed neither support nor courage. Nobody was ready to make sacrifices for unclear returns and without the assurance of commitment by other communities throughout the world to the same level of effort.

Sure, funding for environment-oriented R&D - whatever that covered - was more than doubled; and some symbolic projects were launched, such as Toronto's solar farms. But one of the most visible projects, the 2010 Delhi Commonwealth Games which were touted as the world's first "green games", was quickly exposed as pure "green washing": polluting activity was simply outsourced elsewhere, fuel-powered vehicles were replaced by cars powered by fuel-plant generated electricity, most locals were forbidden to use their cars during the event, etc.

To cap it all, 2011 saw the majority of emerging countries leave the fledgling "Kyoto II" talks, complaining (with some reason) that post-industrial countries were in fact denying them the right to grow in order to protect their own standards of living.

Environmentalists, as well as a large part of the public (especially in the North) watched with disbelief as political institutions and large corporations proved unable to stir the world into an even slightly different direction, despite their best intentions. Incredulity grew when scientists in labs and startups started showing significant results in many areas: nanotech crystals for efficient, flexible and cheap solar panels, small-size and safe nuclear plants, cheaper and safer (although neither cheap nor safe yet) hydrogen production and storage, efficient and versatile isolating materials and fabrics, recyclable oil-free plastics, high-yield and low-input genetically modified crops…

It seems that we knew how to make the world more sustainable. So, why did we not do it? And without ever deciding, people started to do it themselves.

Reboot

Blogs and other websites and Internet-based networks triggered the change. Some, perhaps most, initially focused on the most satisfying task: exposing the bad "eco-practice" of others, especially that of corporations or celebrities (XposeThem.org), denouncing SUV drivers by name (SUVthepla.net), etc. Others were sharing advice, best personal practices, practical and consumer tips for "greasy" (green and easy) living.

Then, an Italian startup created a cute, portable and easy-to-use "Ecogotchis", small, fun personal carbon-footprint calculators that impersonated various animals which choked if you drove, flew or heated your swimming pool too much. These and their many variants - since the design was deliberately open-source - sold by the millions. Thousands of compatible websites recorded Ecogotchi profiles and provided advice and simulations, forums, networking between like-minded owners, etc. Other entrepreneurs seized the opportunity to offer individuals, families and organizations clever and useful ways to reduce their carbon footprint (with instant automated Ecogotchi update): local carbon offset markets in the form of money or community services, open car-sharing mechanisms that paid those who (even very occasionally) took someone else in their car, jobs and places for pooling and sorting recyclable materials…

All this was nice, although very First World and very middle class. It certainly did not change the situation in China, the Middle East or the Parisian suburbs very much. But it slowly changed public spirit. This was most apparent after the deadly bombings that killed 4000 people at the 2012 London Olympics. Public opinion resoundingly rejected the new batch of security measures which their governments tried to enforce; particularly those that would restrict travel or impose strong controls on the Internet. And things quickly went back to normal, except for the fact that several innovative companies came up with novel ways of organizing teleconferences or virtual workspaces, and to teleparticipate in public events, etc.

The network that Ecogotchists and others had formed spanned the globe and included more than a hundred million individuals and organisations. It soon found other uses. After massive floods in Bangladesh killed or displaced millions of people, and while governments and international aid agencies were trying to find the money to act in a serious way, a series of grassroots solidarity initiatives on the Net began collecting money, medicines, blankets, food, mobile communicators as well as organizing missions for physicians, technicians, construction workers and teachers. Sure, some of these initiatives were so amateurish that they sometimes made the situation on the ground worse rather than better, and a few others were scams. But it happened, it helped, and people felt rightly proud about it.

Invention

Some of the technologies that were still in the labs in 2010 started hitting the market near 2015. In affluent suburbs, people proudly lined their roofs with stick-them-up solar coatings, wore intelligent fabric T-shirts in their insulated interiors during winter, and boasted about how few things they owned, renting them or hiring specialized help as needed. The cleverest corporations hired the best and most innovative designers to make sustainable living not only "right", but also pleasant, and an object of pride. Recycling centres became destinations; and products would recycle themselves into useful or funny trinkets. "SharedOne" beacons would broadcast the shareable status of any object, from cars to drilling machines, and families would rate each other by how much they shared.

Innovation was the name of the game. There were several ways of going about it as a company. You could become rich and loathed by coating your innovation with a shiny armour of patents, as BP did with its PersonalHydrogen (TM) system; or you could be loved and not-so-rich by publishing your designs as open-source. A few people managed to be both loved and rich at the same time but eventually, the vast majority would end up one way or the other.

This was a time when thousands of innovative new products and services were marketed every month, often with good chances of success. People were eager for a "cool & good" novelty, "good" meaning demonstrably beneficial to the environment and to oneself. Biotech firms started selling personal enhancement drugs such as memory, sense or stamina extension, as well as others that would colour your skin or eyes, or make them glow in the dark while improving night vision.

The great thing about these drugs was that their effects were reversible - or at least, that was the idea. The intense focus on innovation also resulted in an excessive rush to market untested products. In some cases, this resulted in death or permanent injury for thousands of initial users. However, in general, consumer networks and forums quickly revealed product flaws, forced recalls and compensations, and if needed, exposed irresponsible firms to the wrath of their readers.

Whether in the proprietary or in the open-source universe, however, most innovation happened in a networked way. People tested something very close to their prototype product; others would improve or copy, while still others adapted it to other uses. Networks, both technical and human, became a crucial resource, and Internet neutrality - encompassing by then almost all wired and wireless networks - became a constitutional provision in several countries. Innovation angels, microcredit, local exchange systems and even local currencies, such as Linden dollars or Berliners, flourished and established de facto exchange rates via internet exchanges. Borders, that would otherwise be closed, easily opened for individuals with ideas, capital or good connections.

After a slow start in late 2007, the "One Laptop Per Child" initiative, since then renamed "One Communicator Per Child" (OCPC), slowly made progress. By 2018, when the 400 millionth machine was handed to a child in Botswana, it became clear that, in those countries that had not resisted its western-democracy, constructivist-education slant, OCPC was making a difference. A new class of entrepreneurs, citizens and consumers was emerging in the developing world. They were self-taught by working with the machine and with others as much as they had been taught by teachers who lacked sufficient training and resourcs; and they were reasonably fluent in English since local OCPC translations were poor and unable to keep up with the new applications. Sharing a common culture, they were quickly integrated into the global innovation and discussion networks.

This in turn contributed to faster but still inequitable development in several countries. Birth rates started to decrease slowly. Literacy soared. CO2 emissions were limited by foreign assistance that came with strict conditions, and by customers around the world who could easily check on how the goods they saw in stores were produced.

Self-regulation

By 2025, it was estimated that although governments had taken few successful initiatives, CO2 emissions were 30% below their 2010 levels and that the decrease in emissions was accelerating.

Many people felt that the dynamics that allowed such sweeping changes to take place in the world's production model should also happen elsewhere. Public education systems were slowly deserted in favour of private schools, P2P schools, networked schools, "de-schools" and other means of education. Public transportation systems became at most an information hub and a network of subway tunnels, whereas vehicles, lines, ticketing, etc. were handled by competing companies. Health systems split into myriad of community or specialized schemes and insurance policies. Full retirement pensions almost stopped being an option: only the weakest and the sickest elderly persons could expect support from the large central pension systems. Others have to look for sources elsewhere.

After a series of dramatic incidents with insufficiently tested products, "Eco-labels" that had flourished since 2008 became "Safer Eco-labels". The tacking of labels to an entity or a product was supposed to be preceded by a more or less thorough evaluation of its environmental soundness, work conditions, and user safety. Not all of the labels themselves were safe, since they were run by private companies which competed for the business. But in general, with help from consumer networks, media and - in the last resort - governments, the system worked.

In the summer of 2023, a series of dirty nuke and bioterrorist attacks on 4 continents sent a clear message that innovation had also put new, cheap and efficient means of destruction into the hands of groups who either resented the world's changes, or simply wanted to take advantage of it. An intense world chase, involving law enforcement agencies and savvy netheads, quickly unveiled a network of post-terrorist and mafia groups. It soon became clear that, in a world where everything was in constant flux and control mechanisms were foolproof for no more than a week, such groups multiplied and grew. It became evident in some cases, that they even shared training facilities (and maybe more) with some of the private security agencies to which law enforcement had been outsourced in a majority of states and cities. Although they created stronger independent evaluation bodies, governments were no longer in a position to run large police forces by themselves again.

On a local level, the regulation of most of the urban space was privatized or transferred to communities. This sometimes led to the emergence of barriers or inner-city borders, especially between affluent and poorer communities. Most non-privatized public spaces and services fell into disrepair, sometimes to be replaced by innovative commercial or grassroots substitutes, sometimes not.

Those who were weak, illiterate, chronically sick, or just plain contemplative found life in such a world increasingly difficult. The most mundane transaction required a choice between dozens of providers, channels and pricing options. You could rarely expect any solidarity mechanism to work for you unless your community decided that you needed to be helped, and – apart from assuming that you had a community to go to – it came at a price. A number of religious or traditionalist communities thrived by welcoming those who felt ill-at-ease in a world without any fixed reference points.

Acceleration

FabLabs - small scale automated workshops capable of manufacturing almost any household or lifestyle product, even some smarter versions, after simply downloading the models - started populating mom & pop stores throughout the world in the 2020s, and by 2028, began to be sold in homes. Among the largest manufacturers, several had failed to adapt and thus went down or were forced to sell themselves at a bargain. Philips and Intel were this year's main casualties.

Having privatized many of the services they used to run, and with other public services in disarray for lack of funding and/or users, traditional governments undertook drastic reforms. Their role was mostly focused on ensuring the transparency and loyalty of markets and the performance and neutrality of all networks, and the supervision of the labeling industry. They were often in charge of law enforcement and disaster recovery, and more rarely, of education. The intense scrutiny by citizen networks effectively prevented them from extending their role again, or from thinking long-term. Some governments also reinvented themselves as forums for public discussion and collective decision-making while in other places, other mechanisms were considered to be of better service. As supervisors of the "Safer eco-labels" and other labeling activities, governments also determined which of the most challenging human alterations were the purview of labelled firms: Cloning, gene editing, high-level augmentations…

With public and private funding, the UN was at last tasked with helping to bring Least Advanced Countries into the loop through networking, education and market opening. It was about time. While most of the world thrived, whole countries and entire population groups - even in the richest of countries - were kept or fell into abject poverty. Lagos, Kinshasa, Mexico City and large areas of Los Angeles were under almost official mafia rule. Yet most citizens did not complain: it was unwise to do so and in daily life, any governance was better than none.

By 2030, the world remained animated by a frenzy of innovation with some generally efficient checks and balances to ensure that this frenzied drive did not run amok over too many people. Global warming was happening as planned, and although it was growing fast, the economy was no longer making it worse. Alternative energy sources had reduced the demand on fossil fuels, which had grown decidedly unpopular (and fairly expensive). Water remained a problem, but most countries dealt with it by privatizing their sources, and for those who had the money, it made for more rational use of a resource that had become reasonably expensive.

Affluent people were now looking at ways to benefit from this world by living much longer, looking much better, improving their mental and physical abilities in significant degrees and breeding the cleverest, most beautiful and healthiest babies available. They also tested amazingly powerful and (supposedly) harmless psychedelic hallucinogens. Education, affluence and working women were bringing down birthrates, although the impact of China's de facto elimination of its one-child policy was slowly bringing world population to an impressive total of 9 billion. Overall, it was a pleasant world. If you could afford it.

Amplify, comment and contribute!

You can do that, either by editing the above text, or by providing comments and ideas below.