Difference between revisions of "Regenerative Agriculture- Natural System Services"

m |

|||

| (6 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

<h2>Team Members</h2> | <h2>Team Members</h2> | ||

Safaa AlAdwan <br> | |||

Neil Hazra <br> | |||

Brendan Moroso <br> | Brendan Moroso <br> | ||

Abhipreet Sinha <br> | Abhipreet Sinha <br> | ||

Anne-Floor Vet <br> | Anne-Floor Vet <br> | ||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

Studies from the Soil Health Institute show that regenerative agriculture on average costs slightly less per acre than industrial agriculture, and that two-thirds of farmers can experience improved yields. As it requires less petrochemical-based fertilizers, it also generally has a smaller carbon footprint, with some evidence showing it can even be carbon negative, drawing down carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and fixing it in the pedosphere (soil).<br><br> | Studies from the Soil Health Institute show that regenerative agriculture on average costs slightly less per acre than industrial agriculture, and that two-thirds of farmers can experience improved yields. As it requires less petrochemical-based fertilizers, it also generally has a smaller carbon footprint, with some evidence showing it can even be carbon negative, drawing down carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and fixing it in the pedosphere (soil).<br><br> | ||

According to Project Drawdown 2018, roughly 20% of global croplands were farmed with one or more regenerative agriculture practices. By 2030, this percentage is projected to climb to roughly 55%. Its popularity is growing in-line with an improved understanding of soil and soil health, and the recognition that the extractive nature of industrial farming practices such as monocropping and synthetic fertilizer use can degrade croplands overtime, threatening returns. As a result, many companies have made substantial commitments towards incorporating regenerative agriculture in their supply chains.<br><br> | According to Project Drawdown 2018, roughly 20% of global croplands were farmed with one or more regenerative agriculture practices. By 2030, this percentage is projected to climb to roughly 55%. Its popularity is growing in-line with an improved understanding of soil and soil health, and the recognition that the extractive nature of industrial farming practices such as monocropping and synthetic fertilizer use can degrade croplands overtime, threatening returns. As a result, many companies have made substantial commitments towards incorporating regenerative agriculture in their supply chains.<br><br> | ||

The primary downside to regenerative agriculture is that it is more complex to manage, requiring more engagement and technical knowledge from growers.<br><br> | The primary downside to regenerative agriculture is that it is more complex to manage, requiring more engagement and technical knowledge from growers.<br> | ||

-B Moroso, 2021 <br><br> | |||

This wiki examines several scenarios related to the roll out of regenerative agriculture in the decade from 2022 to 2032. | This wiki examines several scenarios related to the roll out of regenerative agriculture in the decade from 2022 to 2032. | ||

| Line 40: | Line 41: | ||

*[[The role of education in farming / agricultural industry - Abhipreet]] | *[[The role of education in farming / agricultural industry - Abhipreet]] | ||

*[[Increased understanding of soil biology and the impact of deforestation and desertification - Anne Floor]] | |||

*[[Changing role of animal protein on agricultural footprint - Anne Floor]] | |||

==Fishbone Analysis== | ==Fishbone Analysis== | ||

| Line 100: | Line 105: | ||

Surprising 6.5/10<br> | Surprising 6.5/10<br> | ||

Likely 6/10<br><br> | Likely 6/10<br><br> | ||

“If agriculture goes wrong, nothing else would have a chance to go right.” The country grows 95% of its food in the uppermost layer of soil, making topsoil one of the most critical components of our food system. Over the last decade, the government and agricultural industry failed to implement measures to protect the topsoil from conventional agricultural practices, which led to a catastrophic increase in erosion of cropland soils compared to replenishment. A large part of farmlands across the country suffered some degree of desertification, leading to a sharp increase in hunger, with one in five suffering from nutrient scarcity. The future looks bleak, with other alternative farming techniques like hydroponics, urban farming, vertical farming, etc., having failed to reach economies of scale due to a lack of planning and localization of these techniques. <br><br> | |||

The ‘All-in for Regen’ bill was passed in 2022, changing the fate of thousands of farmers across the country. Climate change had been at the centre of conversations across the globe, and after COP26 in Glasgow, most countries pledged to protect the 1.5˚ C commitment. A key challenge for governments was to protect the topsoil while meeting food security targets. The ‘All-in for Regen’ bill helped the farmer community to adopt regenerative practices by 2030 to protect topsoil and improve carbon sequestration. <br><br> | |||

By 2023, activists and farmer communities asked the government for support in adopting farming techniques and requested government address the critical enablers like high equipment costs and lack of knowledge for this change. The lack of readiness and insufficient availability of infrastructure, technology, and education, left 3 million smallholder farmers uncertain about their future. <br><br> | |||

By mid-2024, farmers using conventional agricultural methods were faced with punitive tax increases. The state, on the other hand, continued to be slow moving in building structures to address the nation-wide viability of regenerative agriculture. While farmers struggled to make the transition, the government shored up its position by signing a multi-billion-dollar deal with a Chinese company to supply subsidized equipment to farmers. <br><br> | |||

The year 2025 changed the fate of this initiative. There was a sharp price increase in basic cereals, vegetables, and fruits due to a decrease in yield caused by the transition. In August 2025, a massive scam was exposed in the farm equipment deal. This led to the collapse of the government, casting the future of the “All-in for regen” into doubt. <br><br> | |||

In May 2026, the incoming government faced a series of protests from activists and farmer communities pressuring them to reconsider the terms of ‘All-in for Regen’. Over the next 18 months, through a series of meetings and severe pressure from protesting farmers, the government decided to extend the targets to 2040 of the ‘All-in for Regen’ law, which was approved in the parliament in December 2028. An agreement was made with the farming community to linearly implement alternate agriculture methods with a target of 2040. <br><br> | |||

Millions of farmers had to live in an era of uncertainty and the country suffered an economic crisis, yet the country faces an imminent risk to food security and severe impacts of climate change. We continue to see low adoption rates amongst smallholder farmers and with the current number, achieving the 2040 goals looks like an uphill task. <br><br><br> | |||

<h3>Scenario 4 - Positive Transition</h3> | <h3>Scenario 4 - Positive Transition</h3> | ||

| Line 112: | Line 131: | ||

Surprising 3/10<br> | Surprising 3/10<br> | ||

Likely 5/10<br><br> | Likely 5/10<br><br> | ||

In 2022, no one thought that government would take meaningful action to bring agricultural activities in line with climate change. Popular sentiment was that the powers that be were beholden to petrochemical companies and would never be able to take action that might reduce sales of oil-based fertilizers. This was especially the case after the failure of COP26 to phase out coal. However, a grassroots movement of smallholder farmers in developing economies, which was vastly strengthened when a coronavirus variant crippled long distance food supply chains, successfully lobbied for change. <br><br> | |||

At the end of 2022, new legislation began to emerge, written largely by farmer associations, that set out the fundamental rights of the topsoil. This legislation, while balanced, benefited growers, enabling them to fight consumer packaged food companies and lift the spot market price of most agricultural commodities in exchange for carbon reduction and sequestration. <br><br> | |||

These programs, though bureaucratic and slow to take hold, eventually had notable impacts. Taxes were imposed on extractive industrial agriculture, raising the cost of its products to be more in-line with organic agriculture. Also, certain minimum wage agreements were rolled out to incentive improved practices. Most significantly, new farmers were given access to public sector pension benefits, which incentivized a new generation of farmers to form, attending farm schools and adopting innovative technology and practices in record numbers. <br><br> | |||

By 2026, the amount of carbon dioxide in the earth’s atmosphere had declined notably. This was matched by a concordant increase in the amount of carbon in agricultural topsoil. Significantly, the legislation, through taxes and sanctions, drastically circumscribed the use of feedlots in industrial beef production, which had a large impact on a number of agricultural greenhouse gas emissions. Moreover, in 2028, a farmer in Wisconsin invented a method to improve soil carbon sequestration by a factor of two though the use of certain inputs and practices, which also contributed to declining atmospheric carbon dioxide levels. <br><br> | |||

When the global coronavirus pandemic finally ended in 2029 the state of global agriculture was significantly different than it had been at the start of the pandemic. Owner-operated farm operations had increased, farming had professionalized across most developing economies, and food security was improved amongst nearly all demographic groups. <br><br> | |||

Additionally, a surprising result of the agricultural transition was that, amongst consumers, certain non-communicable diseases such as obesity, heart disease and cancer decreased. This was correlated with a decrease in synthetic fertilizers and pesticides use and improved nutrient density of crops. <br><br> | |||

Lastly, while in 2022 the plight of farmers looked dire, with climate change threatening crop yields and livelihoods around the world, by 2030 the situation was much reversed. Government subsidies helped reduce the risks associated with climate change and regenerative practiced decreased crop susceptibility to extreme weather. In an otherwise gloomy decade, the transition of the agricultural sector stands out in hindsight as the one bright spot, a unique success that set humanity on the path to net-zero. <br><br> | |||

Latest revision as of 08:47, 16 December 2021

Team Members

Safaa AlAdwan

Neil Hazra

Brendan Moroso

Abhipreet Sinha

Anne-Floor Vet

Project Overview

Regenerative agriculture is a set of farming practices that employ nature-based solutions to achieve similar or superior results to those used in current industrial farming practices. By focusing on biological rather than chemical inputs, it takes advantage of services already being performed by plants and animals in a healthy ecosystem, leveraging biodiversity to boost yields. While there is no “official” definition of regenerative agriculture, it generally covers a number of practices including cover cropping, crop rotation and reduced tillage.

Studies from the Soil Health Institute show that regenerative agriculture on average costs slightly less per acre than industrial agriculture, and that two-thirds of farmers can experience improved yields. As it requires less petrochemical-based fertilizers, it also generally has a smaller carbon footprint, with some evidence showing it can even be carbon negative, drawing down carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and fixing it in the pedosphere (soil).

According to Project Drawdown 2018, roughly 20% of global croplands were farmed with one or more regenerative agriculture practices. By 2030, this percentage is projected to climb to roughly 55%. Its popularity is growing in-line with an improved understanding of soil and soil health, and the recognition that the extractive nature of industrial farming practices such as monocropping and synthetic fertilizer use can degrade croplands overtime, threatening returns. As a result, many companies have made substantial commitments towards incorporating regenerative agriculture in their supply chains.

The primary downside to regenerative agriculture is that it is more complex to manage, requiring more engagement and technical knowledge from growers.

-B Moroso, 2021

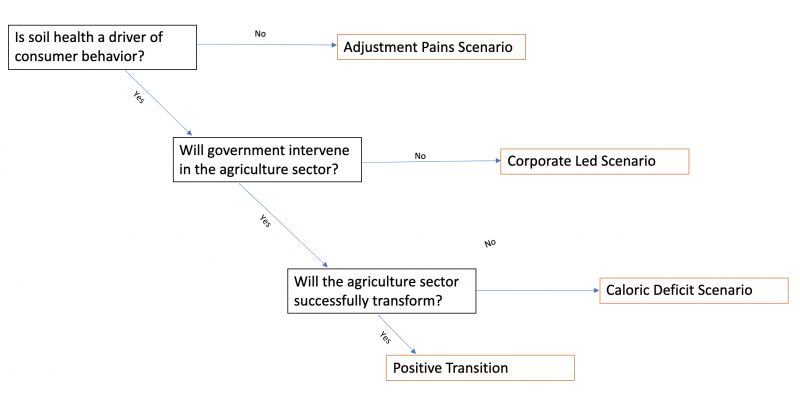

This wiki examines several scenarios related to the roll out of regenerative agriculture in the decade from 2022 to 2032.

Sector Questions

Sector Map

Driving Forces

Fishbone Analysis

Scenarios

Scenario 1 - Adjustment Pains

Key Question: Is soil health a driver of consumer behavior?

Scenario Answer: No

Scenario Stats:

Surprising 6.5/10

Likely 5/10

Nobody would have thought that 2022 was the year that regenerative agriculture broke into the public consciousness. The fervor was intense, every grocery store suddenly had “Healthy Soils” labels on their products, and every fashion company had a clothing line featuring regenerative wool or cotton. But just as quickly as it arose, the fad disappeared. A few reports from NGOs highlighting farmers driven out of business by stringent monitoring requirements or big corporates exaggerating the impact of their practices was all it took to kill the hype. Suddenly consumers no longer cared, and so the “Save our Soils” labels quietly disappeared.

The agricultural industry, which had only begun adjusting to the regenerative movement, began to pivot back. Intercropping and crop rotation, where they had been adopted, were the first practices to be shed. The fact that multi-crop sales agreements and commodity listings never emerged, and that machinery companies were slow to develop farming equipment for blended fields almost guaranteed these practices would be the first to go.

Moreover, new developments in soil biology enabled similar results without needing to adopt complex practices. The industrial production of microbiological soil inputs empowered growers to inorganically boost the microbial health of their soils. Bayer and Syngenta acquired multiple biological farming input companies, eventually developing custom combinations of soil microbes designed to work in conjunction with their chemical inputs.

In the end, winter cover cropping was the only regenerative practice to hold on, and even then, it only persisted in Europe and a handful of other areas. In the US and elsewhere, ground water management legislation, aimed at refilling depleted aquafers, left farmers without enough water to spend on their primary crops, let alone a cover crop. Soil erosion increased, damaging watersheds and causing a year-on-year decrease in salmon redds in major rivers. However, in Europe, where changing Atlantic currents increased the intensity of storms, governments gave subsidies for seasonal cover cropping – viewing it as an affordable way to prevent erosion and flooding. Eventually these payments to landowners were automated through satellite-based crop monitoring, in a process considered by many to be highly biased and political.

The one part of the sector that stuck with regenerative agriculture was the high-end fabric industry. While technically accessible to all farmers, in-practice regenerative certification was only available to owner-operated growing operations, where multi-year commitments on soil growth were possible. While this pushed out food and animal feed, in fabrics the margins were higher and supplier relationships lasted longer. Patagonia in particular continued to be a leader in sourcing and marketing, with its regenerative organic winter clothing line selling out earlier and earlier every year.

By 2032 it was clear that the dream of regenerative agriculture, of growing crops AND growing the soil, would be as niche as organic agriculture. The oracles who had foretold of a future where regeneratively grown, nutrient-dense food would improve both human health AND planetary health were silenced.

However, in several areas, carbon farming as a specialty emerged. Here the stringent land ownership requirements and multi-year sequestration agreements worked in the grower’s favor. Acres of depleted farmland were planted by ever more farmers with specially bred grass blends, just to be knocked down and planted again, with every percentage growth of soil organic matter receiving its carbon credit payment.

Scenario 2 - Corporate Led

Key Question 1: Is soil health a driver of consumer behavior?

Scenario Answer: Yes

Key Question 2: Will government intervene in the agriculture sector?

Scenario Answer: No

Scenario Stats:

Surprising 6.5/10

Likely 5/10

Few people were surprised that 2022 saw the long-expected shift of consumer preference from conventional to green food production. It took almost a decade from the Paris Agreement to see actual changes in consumer behavior, but apparently the extra push from COP26 in Glasgow flipped the coin. Almost all consumer markets were screaming for brands producing their products in a regenerative way with a carbon-neutral footprint and fully transparent supply chains. In particular, the Asian market saw a quick adaptation towards a sustainable food production industry.

Multinationals, facing the brunt of pressure from activist groups like Green Peace, finally made big steps towards carbon-neutral supply chains. They fought to develop local food producers, to limit unnecessary transport distances. Customers, it seemed, would not accept empty shelves in the supermarket as a result of the environmental revolution. Innovative tech companies in the agri-business sector stepped into this gap and profited significantly from these desperate multinationals throwing money at technical solutions to keep their customers provisioned with their usual variety of food products. The introduction of vertical hydroponics inside climate regulated greenhouses made it possible to supply any food with a minimal carbon footprint and without contamination of the soil. Innovation prices had to be paid to adopt quick changes however.

Additionally, most brands and companies invested heavily in marketing campaigns to respond to the environmental desires of the customer. However, without government regulation or clear carbon accounting metrics to measure sustainability, it was difficult to distinguish greenwashing from actual contribution. The battle between the brands became detached from reality, subjective and marketing driven.

2025 was the high-water mark for consumer perceptions of environmental responsibility. According to market research published at the time by the HBR, a majority of the global population was willing to spend significantly more for sustainable and soil protective products. The main winners of consumers' willingness to compromise on price for food produced in a regenerative way were local organic brands and multinationals. Medium-sized food companies, who lacked the capital to change their entire supply chain to meet customer expectations, continued to rely on conventional agriculture and suffered as a result. The lack of governmental subsidies prevented investments towards regenerative agriculture for the companies not supporting the shift themselves. The only option for these companies to compete with was to lower their prices.

By 2027 this consumer-driven revolution led to notable carbon reduction for the agricultural sector. However, that same year also saw the highest global price inflation in the food sector since the 1950s. The divide between price fighters using conventional agriculture and the fancy feel-good brands led to economic inequalities between the population profiting from the environmental revolution and those not able to adapt. By present day this gap metastasized into a problem for our health systems - price fighters were improving their yields through increased use of chemicals and antibiotics, with predictable results. The question then arose, who is finally going to pay for the difference in the future?

Scenario 3 - Caloric Deficit

Key Question 1: Is soil health a driver of consumer behavior?

Scenario Answer: Yes

Key Question 2: Will government intervene in the agriculture sector?

Scenario Answer: Yes

Key Question 2: Will the agriculture sector successfully transform?

Scenario Answer: No

Scenario Stats:

Surprising 6.5/10

Likely 6/10

“If agriculture goes wrong, nothing else would have a chance to go right.” The country grows 95% of its food in the uppermost layer of soil, making topsoil one of the most critical components of our food system. Over the last decade, the government and agricultural industry failed to implement measures to protect the topsoil from conventional agricultural practices, which led to a catastrophic increase in erosion of cropland soils compared to replenishment. A large part of farmlands across the country suffered some degree of desertification, leading to a sharp increase in hunger, with one in five suffering from nutrient scarcity. The future looks bleak, with other alternative farming techniques like hydroponics, urban farming, vertical farming, etc., having failed to reach economies of scale due to a lack of planning and localization of these techniques.

The ‘All-in for Regen’ bill was passed in 2022, changing the fate of thousands of farmers across the country. Climate change had been at the centre of conversations across the globe, and after COP26 in Glasgow, most countries pledged to protect the 1.5˚ C commitment. A key challenge for governments was to protect the topsoil while meeting food security targets. The ‘All-in for Regen’ bill helped the farmer community to adopt regenerative practices by 2030 to protect topsoil and improve carbon sequestration.

By 2023, activists and farmer communities asked the government for support in adopting farming techniques and requested government address the critical enablers like high equipment costs and lack of knowledge for this change. The lack of readiness and insufficient availability of infrastructure, technology, and education, left 3 million smallholder farmers uncertain about their future.

By mid-2024, farmers using conventional agricultural methods were faced with punitive tax increases. The state, on the other hand, continued to be slow moving in building structures to address the nation-wide viability of regenerative agriculture. While farmers struggled to make the transition, the government shored up its position by signing a multi-billion-dollar deal with a Chinese company to supply subsidized equipment to farmers.

The year 2025 changed the fate of this initiative. There was a sharp price increase in basic cereals, vegetables, and fruits due to a decrease in yield caused by the transition. In August 2025, a massive scam was exposed in the farm equipment deal. This led to the collapse of the government, casting the future of the “All-in for regen” into doubt.

In May 2026, the incoming government faced a series of protests from activists and farmer communities pressuring them to reconsider the terms of ‘All-in for Regen’. Over the next 18 months, through a series of meetings and severe pressure from protesting farmers, the government decided to extend the targets to 2040 of the ‘All-in for Regen’ law, which was approved in the parliament in December 2028. An agreement was made with the farming community to linearly implement alternate agriculture methods with a target of 2040.

Millions of farmers had to live in an era of uncertainty and the country suffered an economic crisis, yet the country faces an imminent risk to food security and severe impacts of climate change. We continue to see low adoption rates amongst smallholder farmers and with the current number, achieving the 2040 goals looks like an uphill task.

Scenario 4 - Positive Transition

Key Question 1: Is soil health a driver of consumer behavior?

Scenario Answer: Yes

Key Question 2: Will government intervene in the agriculture sector?

Scenario Answer: Yes

Key Question 2: Will the agriculture sector successfully transform?

Scenario Answer: Yes

Scenario Stats:

Surprising 3/10

Likely 5/10

In 2022, no one thought that government would take meaningful action to bring agricultural activities in line with climate change. Popular sentiment was that the powers that be were beholden to petrochemical companies and would never be able to take action that might reduce sales of oil-based fertilizers. This was especially the case after the failure of COP26 to phase out coal. However, a grassroots movement of smallholder farmers in developing economies, which was vastly strengthened when a coronavirus variant crippled long distance food supply chains, successfully lobbied for change.

At the end of 2022, new legislation began to emerge, written largely by farmer associations, that set out the fundamental rights of the topsoil. This legislation, while balanced, benefited growers, enabling them to fight consumer packaged food companies and lift the spot market price of most agricultural commodities in exchange for carbon reduction and sequestration.

These programs, though bureaucratic and slow to take hold, eventually had notable impacts. Taxes were imposed on extractive industrial agriculture, raising the cost of its products to be more in-line with organic agriculture. Also, certain minimum wage agreements were rolled out to incentive improved practices. Most significantly, new farmers were given access to public sector pension benefits, which incentivized a new generation of farmers to form, attending farm schools and adopting innovative technology and practices in record numbers.

By 2026, the amount of carbon dioxide in the earth’s atmosphere had declined notably. This was matched by a concordant increase in the amount of carbon in agricultural topsoil. Significantly, the legislation, through taxes and sanctions, drastically circumscribed the use of feedlots in industrial beef production, which had a large impact on a number of agricultural greenhouse gas emissions. Moreover, in 2028, a farmer in Wisconsin invented a method to improve soil carbon sequestration by a factor of two though the use of certain inputs and practices, which also contributed to declining atmospheric carbon dioxide levels.

When the global coronavirus pandemic finally ended in 2029 the state of global agriculture was significantly different than it had been at the start of the pandemic. Owner-operated farm operations had increased, farming had professionalized across most developing economies, and food security was improved amongst nearly all demographic groups.

Additionally, a surprising result of the agricultural transition was that, amongst consumers, certain non-communicable diseases such as obesity, heart disease and cancer decreased. This was correlated with a decrease in synthetic fertilizers and pesticides use and improved nutrient density of crops.

Lastly, while in 2022 the plight of farmers looked dire, with climate change threatening crop yields and livelihoods around the world, by 2030 the situation was much reversed. Government subsidies helped reduce the risks associated with climate change and regenerative practiced decreased crop susceptibility to extreme weather. In an otherwise gloomy decade, the transition of the agricultural sector stands out in hindsight as the one bright spot, a unique success that set humanity on the path to net-zero.