Difference between revisions of "Ci'Num scenario 2: Long war(s)"

m |

DanielKaplan (talk | contribs) m |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

**[[Ci'Num scenario 2: Long war(s)|Long war(s)]] | **[[Ci'Num scenario 2: Long war(s)|Long war(s)]] | ||

**[[Ci'Num scenario 3: New enlightenment|New enlightenment]] | **[[Ci'Num scenario 3: New enlightenment|New enlightenment]] | ||

**[[Ci'Num scenario 4: | **[[Ci'Num scenario 4: 100,000 Flowers|100,000 Flowers]] | ||

</small></div> | </small></div> | ||

|} | |} | ||

Latest revision as of 16:09, 18 December 2007

Scenariothinking.org > Ci'Num 07 Homepage > The 2030 Scenarios

|

|

Position in the scenario tree

- Will we have the global organizational capacity to address the overshoot? - Yes

- What is the primary constraint of human activities? - Resources

- What are the main mechanisms for organizing large scale systems? [irrelevant]

Initial Description

The way around climate change and resource shortages is found in simultaneously modernizing rich countries, decelerating the growth of emerging economies-- especially in Asia--and essentially closing off the path of least developed nations to industrial growth. This is achieved by a de facto alliance of governments and large firms in the North that amasses global natural resources and distributes them in an "ordered" way, giving priority to its member countries and their spheres of influence. This creates a permanent state of low-intensity conflict, mostly economic and sometimes military, primarily involving minor countries and using terrorism as a constant threat. Nation-states regain strength as the need grows for internal and external security. International trade is slightly reduced and becomes a political weapon along with the economy in general. This causes the markets to behave erratically and produces inflation and increased savings. Technological developments are fast, unequally shared, and mostly targeted towards security and to surface symptoms of sustainability. The public is incensed by enemies inside and outside the country, and strong opposition movements emerge. Technology also becomes the tool of choice for an emergent counter-culture. The groups anticipate bringing major changes to the state of the world while trying to implement technology, in the meantime, at local, community- or project-based levels.

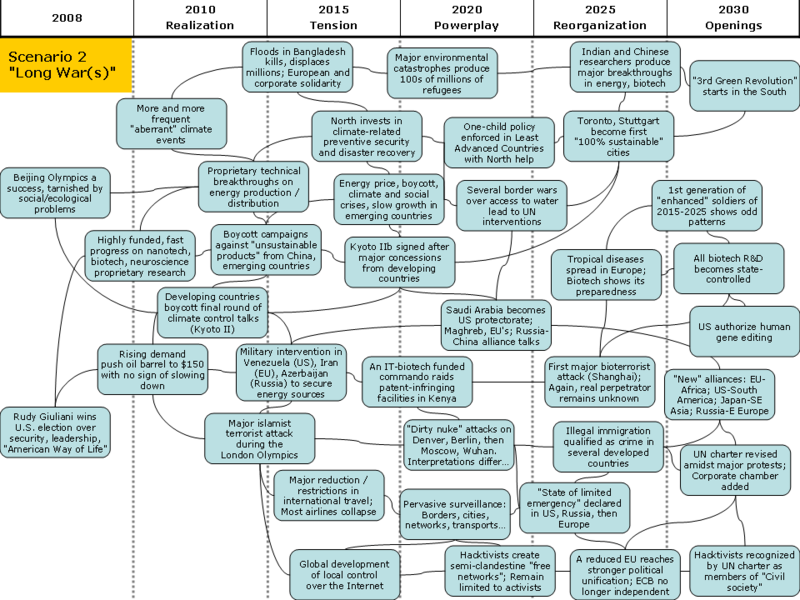

Timeline

(click image to see it full-size)

Full scenario

The 2008 Beijing Olympics sent a shockwave through the world. Visitors and watchers expected a post-communist developing country and discovered huge, clean, modern and secure cities, top-notch facilities and organization, international brands dominating the array of consumer goods in huge shopping malls, Chinese brands producing world-quality hi-tech products, and athletes able to reap medals in almost any category of competition. The new superpower proudly displayed its muscles. It even took advantage of the event's global platform to announce it was abandoning its 1-child-per-family policy in order to stimulate long-term growth and limit future problems related to an ageing population.

The unequivocal success of the Beijing Olympics brought world attention on China, and in the process, made it a country to be feared rather than loved. People were impressed, but, also stunned by the sight of a vast new metropolis in which little of old Beijing remained standing. Global public opinion was incensed by the country's environmental and political conditions: the capital's foul air and reports of worse situations inland by tourists and journalists who traveled within the country; and by news--despite official best efforts at Internet censorship--of social protests that were violently suppressed.

Wake-up Call

In a way, the surprise election of a conservative to the presidency of the United States in 2008 was part of the aftershock. The candidate won by striking fear into the hearts of the electorate about the impending threat from Asia and the need to defend the American Way of Life.

Unexpectedly, the candidate also played the sustainability card. Increasingly, erratic and extreme weather events were making climate change a palpable reality for voters. The candidate made it clear that no matter what the U.S. did to address the problem, it would make no difference for the planet if 2.5 billion Chinese and Indians continued to build coal-fired plants, manufacture chemicals without environmental protections and vastly increase the number of conventional cars and trucks on their roads.

The Kyoto II discussions soon ground to a halt, boycotted not only by the U.S., but also by all major emerging economies who saw it as a brake on their development efforts in order to allow post-industrial countries to preserve their living standards.

Environmentalists and scientists were disheartened. There seemed little hope, at least on the political front, to do much about reversing global warming, or to prepare a smooth transition away from exhaustible and pollutant energy sources.

The answer came from the economic front. Confronted with an ever-growing demand that outstripped supply capabilities, oil producers let prices rise to $150 a barrel, sometimes peaking at $200, all the while using their economic power to bargain for political or symbolic gains, such as hosting UN meetings, or guaranteeing the incumbency of current rulers.

Industrialized countries did not respond as expected. The high cost of oil effected them somewhat less than it did emerging economies, whose competitiveness was reduced. They let inflation rise somewhat, passed energy-saving laws, boosted alternative energies – above all nuclear power - and increased funding for research related to energy and other resources. Consumer campaigns flourished against goods from countries with poor or no environmental controls, resulting in trade tariffs or bans.

All the developing countries felt the pressure, first and foremost, the poorest economies. The impact did not play out as a sudden crisis although some Asian stock-markets slumped rather rapidly. It appeared more as a lower cap that had been imposed on growth rates which were previously close to double digits. Countries in the process of infrastructure development, based on high long-term growth assumptions, became particularly worried.

Low-intensity terrorism was already a fact of life, and in the context of new economic tensions, the devastating bombs that ripped through the 2012 London Olympics did not come as a major surprise. Despite stringent security measures, making the olympics "the most watched event in the history of the world", the bombings killed 4000 people. The origins of the groups claiming responsibility were unknown. The technology was clearly more advanced than was used in other attacks. Still, the groups were never heard of again afterwards.

Tension

By 2015, tension ran high throughout the world, although it was not noticeable in places like Amsterdam, Sidney or NYC. These cities and a number like them in the developed and developing worlds - Mumbai, Sao Paolo - were thriving. They were the centres of corporate power, networked with the world to move goods, people and money, and functioning as sources of new ideas and innovations. Inlaid with technology, these cities enabled invention, innovative services, new public spaces, original art forms and new types of real-virtual relationships – while closely monitoring all spaces for security.

Primarily service oriented, these cities could afford to be more environmentally conscious. Cars remained dominant but adopted new aspects that modified transport: smaller and smarter urban cars, shared cars, on-demand minibuses, and corporate pickups etc..Travel restrictions, imposed by terrorist activities, failed to have much impact on them as well. Already a tightly formed network, using various means of communication, the cities and their corporate entities also had access to the type of on-demand travel services they required.

Corporations readily accepted the general move towards ever-tighter control of the Internet made possible by the London bombings finally made possible, since loud opposition by greying netheads was no longer considered legitimate.

Elsewhere beyond the confines of the world's 200 richest conurbations, things did not proceed as smoothly. Shortly after an explicit US-staged coup replaced Venezuela's Hugo Chavez by a friendlier, Harvard-educated ruler in 2016, Russia took armed control of Azerbaijan's oilfields; while the EU, more carefully but just as decisively, provided the necessary help to the groups who finally toppled the waning mullah power in Iran. OPEC's power was more or less destroyed. Two markets for oil coexisted: bilateral secured long-term agreements provided major economies with reasonably priced oil, while international markets for fossil fuels remained outrageously expensive.

Climate change also began to produce devastating consequences that could no longer be denied. In 2016, after the Philippines was devastated by its third level 5 typhoon in three years, the EU and a group of corporations jointly organized a major recovery effort which made history for two reasons. First, it was the first time a government entity officially mounted a major operation of this kind in conjunction with private corporations. Second, the Phillipines had to agree to new terms for recovery assistance: Its government had to commit to investment in preventive measures (and European technology) against future catastrophes, to open its markets wider to European products, to commit to cleaner and softer growth and to enforce intellectual property rights agreements.

Having invested heavily in energy technologies as well as radar-based defences for climate-related events, the West began using its technology as a bargaining tool for countries that suffered most from climate change impacts.

High energy costs, consumer boycotts, pollution and climate problems began to impact heavily on emerging economies. Some continued to grow, albeit in a disjointed and much slower way. Others went into decline amidst social unrest and political instability, which further exacerbated the problems. Foreign investment became more scarce and were weighted with conditions. The largest cities in the developing world plunged into anarchy, while their population kept growing. New industrial cities built hastily at the turn of the 21st century with little thought to quality and soundness fell into disrepair and quickly degraded.

Powerplay

As a consequence, in 2019, Brazil, China and India, soon followed by most of the developing world, signed the "Kyoto IIb" (K2B) agreement, which had largely been drafted by experts from the post-industrial world. According to K2B, all countries committed to sharp reductions in energy consumption and CO2/particle emissions. But there were more concessions to K2B. Western countries - and some corporations, which were actually signatories - agreed to share their technology and resources with developing countries to mitigate against climate impacts and related social unrest, provided these countries signed on to a sweeping reform agenda: market openness, liberalised foreign investment, protection for intellectual property rights, reduced emigration, police and judicial cooperation… Several countries also traded higher western help in return for enacting a "one-child-per-family" policy.

The expansive new rules were also rigidly enforced by whatever means made sense. In 2022, an armed commando unit, funded by seven IT and biotech firms raided a group of patent-infringing industrial complexes in Nairobi, destroying the facilities and holding the government hostage until it formally committed to the K2B agenda. A UN special force, funded by America, the EU and Japan and supported by several multinational corporations, was tasked with settling the growing number of border conflicts taking place over access to resources, especially water. Country borders, public spaces, ICT networks, and transportation systems were all under strict surveillance.

Under K2B, the major industrial countries began to organize their spheres of influence. Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries became de facto US protectorates. The Maghreb became the same with respect to the EU, while Russia reasserted a not-so-light control over a large number of former Soviet republics.

The birth of this new, de facto world order met with strong resistance. While the World Economic Forum supported it, the World Social Forum - having recovered from its earlier financial crisis - became a vocal, effectively networked, savvy opponent. It could use the semi-clandestine "free networks" that kept emerging over the Internet, despite all attempts at control. Choosing other forms of opposition, alternative, neo-hippie communities left cities and committed to traveling the world on foot, horse or bike.

Many other political, economic and religious groups resisted the new world order for various reasons and, sometimes, in violent ways. This opened the door to all kinds of political manipulations and/or suspicions. Thus, when a devastating series of "dirty nuke" attacks assailed Denver, Frankfurt, St Petersburg and Wuhan in 2023, there were very different speculations as to the perpetrators: Who stood to gain from a continuous state of fear? The US and Russia, followed by most EU countries, declared a state of "limited emergency" which was only - and somewhat partially - lifted around 2027-2030. Surveillance became even more ubiquitous and permanent. Illegal immigration became a highly punishable crime.

It was harder and harder to migrate from the developing world to the post-industrialized world. Those who were given a chance to study or work for some time in the North started forming a new, "globalized class", whose ties with international business and government communities were sometimes stronger than with their fellow countrymen.

Reorganization

During that period, science and technology made great strides, although mostly in the close confines of laboratories and private colloquia, subject to strong security and secrecy rules. The research agenda was mostly defined by four groups: Military and law enforcement agencies, energy agencies and corporations, health agencies, and nano-bio-IT multinational corporations.

IT managed to smartly combine increased security with innovative capabilities. Pervasive sensors, actuators and interactive interfaces of all kinds provided a ubiquitous grid of information closely related to physical and relational spaces, allowing the advent of many innovative commercial services as well as ever tighter surveillance and control. Many of those who felt ill-at-ease with this emerging world came to populate the real-virtual social spaces of free expression and behaviour. These spaces were tolerated, sometimes even encouraged, by governments since they were also very easy to monitor.

Nanotech, biotech and neuroscience products slowly trickled down from their initial uses by the military, law enforcement or nuclear agencies to be employed by the general public. Corporations would subsidize employees willing to gain new capacities through implants or highly selective drugs. Those who could afford it could make sure their offspring were endowed with as many beneficial genetic traits and with as few defects as possible. In fact, prenatal screening for selected potential problems became compulsory in several countries. New drugs and preventive medicine played a major role in raising life expectancy - and extending the "health expectancy" of elderly people in good health - beyond the century; again, for those who could afford the full treatment. The idea of a fixed retirement age became passé in ruling circles, sometimes to the dismay of the younger generation whose prospects for upward social mobility seemed indefinitely delayed.

The biotech industry actually showed its preparedness on two dramatic occasions. One was the first major bioterrorist attack that took place in Shanghai in 2026; the other was the successive outbreak of tropical diseases in southern Europe, where the population was genetically unprepared for germs that once prevailed only in regions several thousand miles southward. In both cases, pharmaceutical firms were able to diagnose the strains, and to mass-produce and distribute antidotes in a matter of days, saving tens of thousands of lives. Some observers noted, however, that when poorer populations faced decimation by similar diseases, the same companies failed to show the same level of diligence.

Taking advantage of superior technologies, developed by the corporations they were associated with, Toronto and Stuttgart declared themselves to be the world's first "100% sustainable cities" in 2022. Using a combination of alternative resources, materials and mechanisms - such as a mix of alternative energy sources, decentralized distribution mechanisms, efficient materials, building and engineering techniques, new forms of public transport, sequestration and recycling facilities as well as pervasive control networks - the cities claimed they were able to produce more energy than they used, and that they released no CO2 and practically no hazardous waste, either in the air or in the ground.

That claim was, however, contested by a group of researchers who showed that the result was partly achieved by outsourcing polluting activities to other parts of the world. In fact, several public universities (usually the poorer ones, since the educational system has become highly competitive) had become a networked locus of intellectual dissent. While trying to lend alternative views to scientific and political discussions in the North, they also (prudently, since careless disclosure of scientific research results is an punishable offense) networked with colleagues in the South in order to facilitate the circulation of knowledge.

Openings

Around 2025, these initiatives started to bear fruits. In a visibly coordinated manner, researchers in India, China and Chile produced interesting breakthroughs in renewable energies as well as high-yield, low-input genetically modified crops and livestock. India immediately announced its intention to lead a "3rd Green Revolution" and to share it with other emerging countries. Western corporations tried to contest the discoveries, claiming that they infringed on the thousands of patents that they had filed over the previous decades. But the move was well prepared in legal and diplomatic terms. Further, it was difficult to argue that this was not what Kyoto IIb was all about, at least officially!

Meanwhile, the first generation of "enhanced" soldiers, policemen, firemen and top executives of 2025-2025 started showing odd pathological symptoms. Biotech and health-oriented nanotech in the North became even more state-controlled and subject to prior testing, and some information was allowed to circulate more freely. However, not all countries were ready for this development: the authorization of private-purpose human gene editing by the US, Japan and Korea in 2027 met with fear and awe in the rest of the world.

The geospheres of influence were expanding, becoming more intertwined, and therefore, somewhat looser in some ways. The US rediscovered its link with South America. The EU – now depleted in its ranks by the exit of some of its eastern member-states, but much more politically unified – recovered its links with Africa, while Japan renewed its ties with Southeast Asia despite grumblings from a weakened - but still commanding - China.

Faced with the prospect of becoming irrelevant, after having been the global overseeer and the last resort for cooperation in a conflict-ridden world, the UN decided to reinvent itself. It created an official Corporate Chamber and another for regions and cities. States protested, but they were quickly shut down by the firms and the metropolitan centers that were the states' true ganglion. Even the hacktivists who had kept the Internet more or less open during these years were given official UN recognition as members of the "Civil Society". The goals and capacity of this new UN were still unclear; but it certainly reflected what the world had become in a more faithful way.

By 2030, the world economy was closer to sustainability than it had been for a century. It was also slowly moving away from a situation of permanent conflict and major existential risks. But there were still dangers. Sustainability had been achieved first by maintaining billions of people in poverty, and then only, and only partially, by technical and organizational progress. Larger than ever economic and political alliances were vying for power, with economic and military means that were more potent than those of any individual country except the USA. Corporations had become an almost autonomous power, even able to muster military force. Biotech had generated the means to produce cheap and very lethal weapons. The younger generations in the North and (even more) in the South were growing restless at the sight of a world ruled by a powerful caste of older and older people.

The world had succeeded in wrestling itself away from global environmental collapse. It now had to build itself as a place of well-being.

Amplify, comment and contribute!

You can do that, either by editing the above text, or by providing comments and ideas below.